(Original Article Published via RawFoodForPets.com) (Featured Image Credit: Michael Blann / Getty Images)

Dogs, subspecies of wolves, Canis lupis familiaris

It is not difficult to see why there is so much debate about the classification of the species “dog”. Given all of the research performed and published to validate the introduction of carbs and starches into the “dogs” diet, it is rather fallacious. What science has taught us thus far, is that dogs do have extra copies of the gene for amylase, and it does have the ability to produce 28 times more amylase than wolves. Is 28 times more significant, and can we then surmise that the wolf can also produce amylase? Science has also determined that the species “dog” produce 12 times more maltase-glucoamylase, which converts maltose into sugar, due to mutations in the gene for this enzyme. Does these mutations warrant the species “dog” to be classified as an omnivore, and validate the current inclusion of starches and carbs in commercial diets?

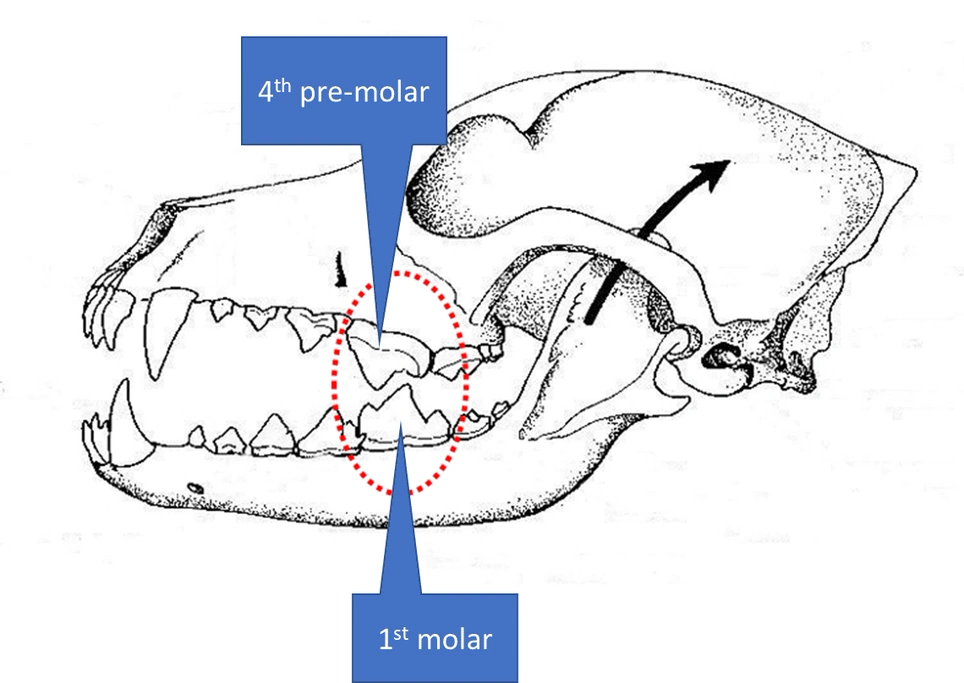

Let us, for a moment, consider the dentistry of our species “dog” (PDF). Puppies have 28 teeth, and just like huuman babies, they are prone to losing baby teeth and replacing them with permanent adult teeth. Adult dogs are equipped with 42 teeth comprising 12 incisors, 4 canines, 15 pre-molars and 10 molars. More precisely, there should be 6 incisors, 2 canines, 8 pre-molars and 4 molars in the upper jaw, and 6 incisors, 2 canines, 8 pre-molars and 6 molars in the lower jaw.

By taking a look at the term “carnassial” we can already conclude that the current classification of the “dog”, as an omnivore, can be misleading. According to the American Heritage Dictionary, the term carnassial derives from the French word “carnassier”, which means carnivorous. The term carnassial teeth therefore refers to teeth specifically designed for shearing flesh. For good reason, the dog’s carnassial teeth are the largest of all. The carnassial teeth are purposely crafted so dogs could shear through flesh, tendon and muscle, and crack bones.

The species “dog” has no flat molars because nature did not intend for him to eat much in the way of plant matter. He also has powerful jaw and neck muscles that aid in pulling down and consuming prey. The jaws open very wide to accommodate whole chunks of meat and bone, and move only up and down (not side to side), because they are designed for crushing.

In contrast, some omnivores and herbivores have jaws that permit the lateral (side-to-side) motion necessary for grinding plant material. The carnivores stomach is short and simple in design, and also very acidic. It is meant to move food quickly through, and to deal with the pathogens found in fresh whole prey, which is not clean meat.

If we consider the 2013 study titled The genomic signature of dog domestication reveals adaptation to a starch-rich diet that has become wildly popular with the processed pet food and dogs are omnivores, not carnivores supporters, the authors point is valid: dogs are not wolves. However, the fact remains that dogs are a subspecies of wolves: Canis lupis familiaris – the familiar (i.e. domesticated) wolf, and in our minds the presence of the carnassial teeth is very much a visual reaffirmation.

This specific study has become dogs are omnivores, not carnivores supporters bible, providing proof that dogs should be eating starchy, carb-heavy diets instead of protein-rich animal meat-based diets. But if we consider our examples on genetic differences, variations and similarities, then one has to question the current classification and stance regarding the species “dog”. In real terms, all the study validates is that the species “dog” body has some capacity to adapt to the food it eats. It certainly does not prove that it is good for dogs to have more starch in their diet. We do not want to encourage our pet parents to feed biologically inappropriate diets because their dogs body may or may not have the ability to adapt.

The study does show there are genetic differences between dogs and wolves, which should not be a surprise to anyone. Dr. Doug Knueven, whom has done an independent review of the study, points out that dogs are indeed undergoing an evolutionary process, but what we might not understand about this process, is that NO individual dog is evolving. Feeding dogs a starch-rich diet will not cause them to evolve to change their genetic code to be able to handle it better.

To gain some insights into some of these evolutionary principles, do some research on Dr. Dimitry K. Belyaev, Director of the Institute of Cytology and Genetics in the former U.S.S.R., where he remained director through 1985. In 1959, Dr Dimitry began investigating the genetics of dog domestication by selectively breeding another canine, silver foxes, from local fur productions farms in the former U.S.S.R. The experiment was commonly referred to as the Fox-Farm Experiment. Over relatively few generations, the foxes displayed tremendous changes in behavior and appearance. The researchers’ data was showing how selection for a single characteristic was also related to a number of other unselected traits. A question not answered was: where do we draw the line between domesticated and wild species? In domesticated animals, genetic variations are fixed after natural selection weeds wild versions out of the gene pool. Science tell us that is why dogs do not suddenly become wild if they are not born around humans. But this is not the case with the tame foxes, some of which still carry wild versions of genes that they can pass along to their kits.

The way we understand evolution to work, is there are certain mutant individuals say a group of dogs that have a mutation that allows them to digest starch better than most dogs. Those individuals might adapt to better process a high-starch diet. They will reproduce, which means the mutated gene they carry will become more common in the future; their offspring may also process starch more efficiently. But all the rest of the dogs will continue to not do well on a high-starch diet.

The dogs with the mutated gene can survive on it, but the non-mutant do not do well, and that can lead to future health problems, including the biological consequences of feeding an inappropriate, high-starch diet to a carnivore. The study unfortunately did not address what happens after the glucose in high-starch diets hits the dogs systems, triggering a cascade of inflammatory processes.

What research does show is that if dogs are fed a grain-based diet for decades, over time they develop the ability to process some starch, or do they? Perhaps that ability has always been present, a design for survival. This process is called an evolutionary adaptation. It’s a good thing these adaptations occur, because if animals didn’t adjust to some degree to changing environments and the species-inappropriate diets they’re fed, they would die off in large numbers and ultimately become extinct.

Perhaps our species “dog” ability to process some carbs has always been present, a design for survival instead?

But what about other carnivorous species?

We wondered if the study on dogs are unique, and if conditions dictated adaptation, would “evolution” or “designed for survival” allow for similar adaptations in other carnivores. In 2003 a study titled “Comparative nutrient digestibility of arctic foxes (Alopex lagopus) on Svalbard and farm-raised blue foxes (Alopex lagopus)” (PDF) we found some answers. The food availability for the arctic fox [Wikipedia] on Svalbard varies with season. Seabirds and eggs are main food sources in summer, and terrestrial birds and carcasses of Svalbard reindeer and seal are dominating during winter. We can therefore conclude that the arctic fox has a diet consisting mainly of protein and fat of animal origin and nothing or very little from vegetable sources.

As a result, we believe the arctic fox conform with the carnivores classification, both in dental and diet. The farmed blue fox, on the other hand, is raised on a diet with considerable higher amount of carbohydrates coming from grain or other vegetable sources. According to feeding recommendations from the study, carbohydrates accounted for as much as 35% of metabolized energy (ME) in the diet of farmed blue foxes. It should be noted that both specie of fox was fed with the same diet for the purpose of the study. The outcome of the study was that (wild or non-domesticated) arctic foxes have an ability to digest carbohydrates, even though digestive capacity for carbs in the blue foxes (farm-raised) was higher. The study unfortunately did not address what happens after the glucose in high-starch diets hits the fox’s systems, triggering, what we would anticipate, a cascade of inflammatory processes.

And what about other species in the Order Carnivora? Turns out several similar studies have been done “comparing digestive efficiency of extruded diets with ferrets and minks (Mustela putorius furo)” and “Comparison of feed preference and digestion of three different commercial diets for cats and ferrets“, “Palatability and digestive tolerance of a new high protein / low carbohydrate commercial dry diet in adult ferrets“, “Comparative digestibility of nutrients and energy in ferrets (Mustela putorius furo), mink (Neovison vison) and cats (Felis catus)“. In all of the studies, our carnivorous friends demonstrated their ability to digest carbohydrates when the need arisen.

We don’t believe the presence of alpha-amylase warrant a reclassification of the arctic fox, or the blue fox, or ferret, or mink from carnivore to omnivore. We believe the presence of carnassial teeth in the species “dog” trumps the presence of the dietary enzyme amylase, as the fox shares the same or similar attributes, and still the fox is classified as a carnivore.

The question we ask then, is why do we insist on classifying the species “dog” as an omnivore? We all agree that the species “dog” is a scavenger by heart, and thrive on a primarily animal-based protein diet. Some even refer to the species “dog” as scavenging carnivores as a result. The jest of the studies presented also indicate that if need be, the dog, like the fox, can survive on non-specie appropriate diets.

But is that wise?

One of the arguments for feeding dogs grain or plant-based or even vegetarian diets is the distinction between obligate and scavenging carnivores. It’s assumed, since dogs aren’t strict carnivores like cats, they can easily transition to a meatless diet.

We then also need to ask why there is very little published research on biologically appropriate diets for cats and dogs. We believe this is a huge obstacle toward helping more veterinarians and pet owners learn the benefits of nutritionally balanced, real and fresh food diets.

The direct result due to the lack of research, is that studies of biologically appropriate diets for humans and rodents have been extrapolated to cats and dogs. However, humans and rodents are omnivores (both plant and meat eaters), whereas cats are obligate carnivores, meaning they need animal protein, fats and a moisture-rich diet to survive.

This leads to another question we should all be asking, which is why, if the processed pet food industry recognizes this distinction, it persists in producing biologically inappropriate, plant-based dry diets for cats?

It is also true that the dog and cat are both adaptable creatures and will not voluntarily starve themselves when fresh meat is not available. This means that if you feed them carbohydrate for economic reasons they will eat it and most likely survive with the minimal amount of protein they get from it. But do they actually thrive (live long and healthy lives) consuming a biologically incorrect diet? Pet feed manufacturers claim all kinds of success in their advertisements; however, they do not factor in all of the medical problems or the potential loss of life years associated with feeding a biologically incorrect diet.

Just because dogs fed plant-based diets are able to stay alive doesn’t make them omnivores. Taxonomically, dogs are in the Order Carnivora and the family Canidae. We prefer the term facultative carnivores when we address the dietary needs of the species “dog”. The facultative carnivore, is a carnivore that does not depend solely on animal flesh for food but also can subsist on non-animal food, as demonstrated by the research on the arctic fox and farm-raised blue fox.

Our Conclusion?

Although they differ somewhat from cats, we believe the species “dog” should be considered carnivores. Based on their dentition, as well as the length of their canine teeth, a shortened gastrointestinal tract, versus the longer GI tract of an omnivore or herbivore. A dogs teeth reflect the mechanics of the ripping and tearing of food. In addition, dogs do not have amylase in their saliva, like an omnivore and herbivore would have. The relative inability to convert plant-based sources of Omega-3 fatty acids into EPA and DHA is also a strong indication of carnivore status.

We trust that our simplistic applications of anatomical differences are not viewed as fallacious. What we have been able to learn and assimilate from research available online is that several key anatomical features separate dogs and cats from omnivores and herbivores. These features we believe classify them as carnivores with an adaptation for an almost exclusively meat-based diet.

Stomach Type and Length:

- Dogs and cats possess a short, simple gastro-intestinal tract. Because meat is easily digested (relative to plants) their small intestines are short;

- A high concentration of stomach acid helps to quickly break down proteins, this is generally due to carnivores having a stomach acidity of about pH1 – compared to humans at pH 4 to 5.

Teeth and Jaws:

- A large mouth opening with a single hinge joint adapted for swallowing whole chunks of meat;

- Short and pointed teeth designed for grasping, ripping and shredding meat, not grinding grains;

- Teeth and jaws designed to swallow food whole, not for chewing or crushing plants.

Digestive Enzymes

- Adapted to break down protein and fat from meat, not plants or grains, the saliva of dogs and cats does not contain the digestive enzyme amylase;

- Carnivores do not chew their food. Unlike carbohydrate-digesting enzymes, protein-digesting enzymes cannot be released in the mouth due to the potential of damaging the oral cavity (term referred to is auto digestion);

- As a result, carnivores do not mix their food with saliva, they simply bite off huge chunks of meat and swallow them whole (wolfing it down).

Based on their digestive tract adaptations, we believe that dogs are scavenger (or facultative) carnivores, while cats are true (or obligatory) carnivores. A scavenger is an animal who will sort through discarded material or eat dead carcasses to take advantage of what it finds. Although dogs would prefer meat, they can survive on whatever is available.

For the purpose of our hypothesis, we therefore adopt the concept or definition of:

- obligate carnivores for cats;

- facultative carnivores for dogs.

References

- Axelsson E, Ratnakumar A, Arendt M-L, et al. The genomic signature of dog domestication reveals adaptation to a starch-rich diet. Nature. Published online January 23, 2013:360-364. doi:10.1038/nature11837

- Eide NE, Stien A, Prestrud P, Yoccoz NG, Fuglei E. Reproductive responses to spatial and temporal prey availability in a coastal Arctic fox population. Journal of Animal Ecology. Published online December 23, 2011:640-648. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01936.x

- Fuglei E, Aritsland NA, Prestrud P. Local variation in arctic fox abundance on Svalbard, Norway. Polar Biol. Published online December 17, 2002:93-98. doi:10.1007/s00300-002-0458-8

- Sá FC, Silva FL, Gomes M de OS, et al. Comparison of the digestive efficiency of extruded diets fed to ferrets (Mustela putorius furo), dogs (Canis familiaris) and cats (Felis catus). J nutr sci. Published online 2014. doi:10.1017/jns.2014.30

- Fekete SGy, Fodor K, Prohaczik A, Andrasofszky E. Comparison of feed preference and digestion of three different commercial diets for cats and ferrets. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. Published online April 2005:199-202. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0396.2005.00536.x

- Linsart AJ, Figuera J, Fournel S, Ségalen C, Batard A, Navarro C. Palatability and digestive tolerance of a new high protein/low carbohydrate commercial dry diet in adult ferrets. Revue Varinaire Clinique. Published online December 2018:107-113. doi:10.1016/j.anicom.2018.08.003

- Sundling L, Ahlstrøm Ø, Tauson A-H. Comparative digestibility of nutrients and energy in ferrets (Mustela putorius furo), mink (Neovison vison) and cats (Felis catus). In: Proceedings of the Xth International Scientific Congress in Fur Animal Production. Wageningen Academic Publishers; 2012:112-120. doi:10.3920/978-90-8686-760-8_16

- Pajic P, Pavlidis P, Dean K, et al. Independent amylase gene copy number bursts correlate with dietary preferences in mammals. eLife. Published online May 14, 2019. doi:10.7554/elife.44628